Company Towns and Coal Camps: Life in the Appalachian Mines

Introduction

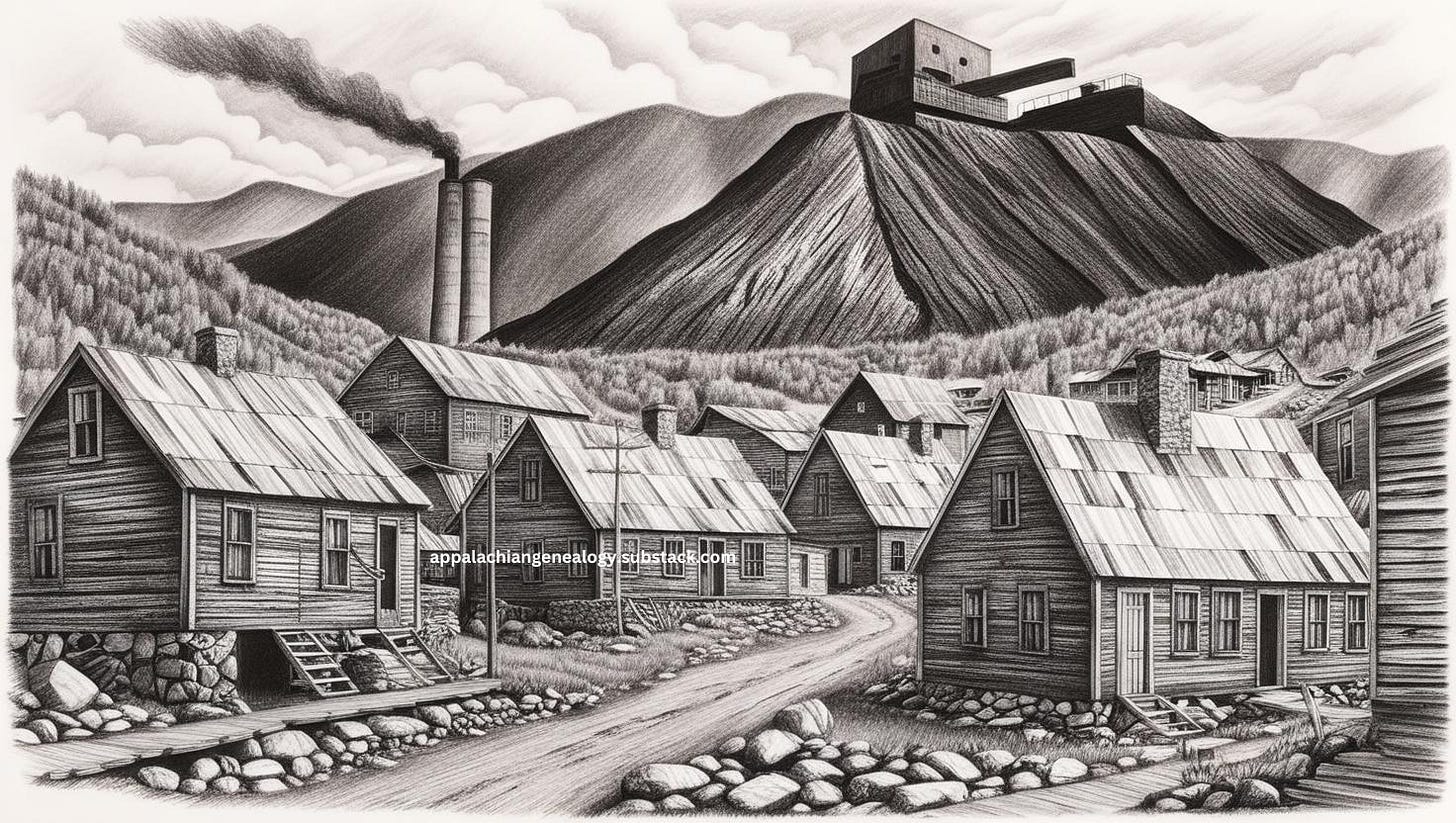

The rise of coal mining in Appalachia brought about a unique social and economic structure: company-controlled towns. These settlements, often called coal camps, were established by mining companies to house workers and their families. Unlike independent communities, company towns operated under the strict control of employers, influencing every aspect of life from housing to commerce. While these communities provided job opportunities, they also led to economic exploitation and social struggles that shaped the region’s history.

The Rise of Company Towns

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the demand for coal surged, driving the expansion of mining operations across Appalachia. To accommodate the growing workforce, companies built entire towns near mining sites. These settlements included homes, stores, churches, and schools, all owned by the coal operators (Corbin, 1981). Workers often lived in company-owned houses, shopped at company stores, and were paid in scrip, a form of currency redeemable only within the town (Shifflett, 1991).

The design of company towns varied, but most featured a hierarchical layout reflecting social divisions. Higher-ranking officials lived in well-constructed homes with modern amenities, while miners and laborers occupied small, basic dwellings (Lewis, 2003). Despite these disparities, mining families built strong community bonds, often relying on each other in times of hardship.

Economic Control and Exploitation

Company towns were structured to maximize profit for mine owners while maintaining control over workers. By issuing wages in scrip instead of cash, employers ensured that workers remained dependent on company stores, where prices were often inflated (Long, 1989). This system, known as the "truck system," left many miners in perpetual debt, unable to accumulate savings or financial independence.

The lack of economic freedom extended to housing as well. Rent was deducted from wages, and families who opposed company policies risked eviction. The interwoven economic dependency created an environment where dissent was nearly impossible without severe consequences (Tams, 1963). These practices fueled resentment and eventually contributed to labor movements demanding fair wages and better working conditions.

The Hardships of Mining Life

Living and working conditions in coal camps were grueling. Miners faced dangerous work environments, often deep underground in poorly ventilated tunnels. Accidents, explosions, and health hazards such as black lung disease were common (Dunaway, 1996). Safety regulations were minimal, and company priorities often focused on maximizing coal production rather than worker welfare.

Families of miners endured their own challenges. Women and children played essential roles in maintaining households, often supplementing family income through gardening, sewing, or taking in boarders (Eller, 1982). Education opportunities were limited, as children were sometimes required to work in mines or support family efforts to survive. Despite these hardships, cultural traditions, music, and storytelling flourished, providing a sense of identity and resilience.

Labor Movements and Resistance

As exploitation became more apparent, miners began organizing to demand better wages, improved conditions, and the right to unionize. Early efforts to form unions were met with fierce resistance from coal companies, which employed armed guards and strikebreakers to suppress activism (Corbin, 1990). One of the most significant conflicts was the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, where thousands of miners clashed with law enforcement and private security forces in a struggle for union recognition (Savage, 1990).

The rise of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) played a crucial role in advocating for miners’ rights. Through strikes, protests, and legal battles, the UMWA secured labor protections such as the eight-hour workday and safer working conditions (Shifflett, 1991). These hard-fought victories helped dismantle some of the most exploitative practices in company towns.

The Decline of Company Towns

By the mid-20th century, technological advancements and shifts in economic policies led to the decline of company-owned towns. Mechanization reduced the need for large labor forces, and improved transportation networks allowed workers to commute from independent communities (Lewis, 2003). Additionally, federal regulations, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, established protections that weakened the control of coal operators over workers’ lives (Long, 1989).

As company towns disappeared, many former mining communities faced economic collapse. With coal employment dwindling, families struggled to find alternative sources of income. Some towns transformed into ghost towns, while others adapted by diversifying local economies through tourism, crafts, and alternative industries (Dunaway, 1996).

Lasting Impact on Appalachian Culture

The legacy of coal camps remains deeply embedded in Appalachian culture. Many families still trace their ancestry to miners who lived and worked under the company-town system. The struggles and triumphs of these workers are commemorated through music, literature, and oral histories, preserving the resilience of past generations (Eller, 1982).

Efforts to document and preserve the history of coal camps have gained momentum in recent decades. Museums, historical societies, and heritage trails highlight the experiences of mining families, ensuring that their stories remain an essential part of Appalachian identity (Savage, 1990).

Conclusion

The rise and fall of company-controlled towns in Appalachia reflect a broader narrative of economic opportunity, exploitation, and resilience. While coal mining provided jobs and shaped the region’s culture, the restrictive and often harsh conditions of company towns left a lasting impact on generations of workers and their descendants. Understanding this history offers valuable insight into the socioeconomic struggles of mining communities and the enduring strength of Appalachian identity.

References

Corbin, D. A. (1981). Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922. University of Illinois Press.

Corbin, D. A. (1990). The West Virginia Mine Wars: An Anthology. Appalachian Editions.

Dunaway, W. A. (1996). The First American Frontier: Transition to Capitalism in Southern Appalachia, 1700-1860. University of North Carolina Press.

Eller, R. D. (1982). Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South. University of Tennessee Press.

Lewis, R. (2003). Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880-1920. University of North Carolina Press.

Long, P. (1989). Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America’s Bloody Coal Industry. Paragon House.

Savage, L. (1990). Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920-21. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Shifflett, C. (1991). Coal Towns: Life, Work, and Culture in Company Towns of Southern Appalachia, 1880-1960. University of Tennessee Press.

Tams, W. P. (1963). The Smokeless Coal Fields of West Virginia: A Brief History. West Virginia University Press.